My 3rd Great Grandfather.

JOHN SUMMERFIELD born 22nd October 1793 in Brereton cum Smethwick and died in Bradford, Manchester 17th November 1876. He married Hannah Grimshaw, daughter of George Grimshaw and Hannah Grimshaw, on 11th June 1813 in the Cathedral and Collegiate Church of St Mary, St Denys and St George, in Manchester. She was born in June 1796 in Lancashire. John Summerfield and Hannah Grimshaw had the following children:

- SAMUEL SUMMERFIELD was born 5th December 1813, Clayton Demesne, Manchester.He married Nancy Mather 21st September 1835 at Manchester Cathedral. Samuel was buried in Bradford, Manchester aged 74 years on 9th January 1888.

- WILLIAM SUMMERFIELD was born in 23rd July 1815 in Openshaw, Manchester. He married Alice McCarty, daughter of John McCarty on 19th April 1846 in Manchester Collegiate Church (later Manchester Cathedral). She was born in Ireland.

- MARY SUMMERFIELD was born on 5th June 1817 in Openshaw, Manchester.

- MARGARET SUMMERFIELD was born about 1820 in Openshaw. She married Peter Owen, son of William Owen and Catharine Owen on 12th July 1840 in All Saints, Manchester. Peter was born in 1818 in Manchester, Lancashire.

- ELIZABETH SUMMERFIELD was born on 4th November 1821 in Lancashire.

- JOHN SUMMERFIELD was born in 1824 in Openshaw, Lancashire. He married Matilda Dutton, daughter of John Dutton on 30th June 1850 in Manchester, St Mary, St Denys and St George, Lancashire. She was born in 1827 in Manchester, Lancashire.

- HANNAH SUMMERFIELD was born in 1828 in Manchester, Lancashire. She married Robert Gregory, son of Elizabeth on 4th March 1849 in Manchester, St Mary, St Denys and St George, Lancashire. Robert was born in 1827 in Manchester, Lancashire.

- SARAH SUMMERFIELD was born on 9th March 1830. She married William Bell, son of George Bell on 25th December 1861 in Manchester, St Mary, St Denys and St George, Lancashire. William was born about 1830 in Manchester.

- JANE SUMMERFIELD was born on 1st December 1833 in Openshaw, Manchester, Lancashire. She died in Quarter 1 1877 in West Hartlepool district. She married James Mayoh, son of James Mayoh and Jane Greenhalgh on 10th November 1861 in Manchester Cathedral. James was born in 1838 in Turton, Lancashire. He died in 1882.

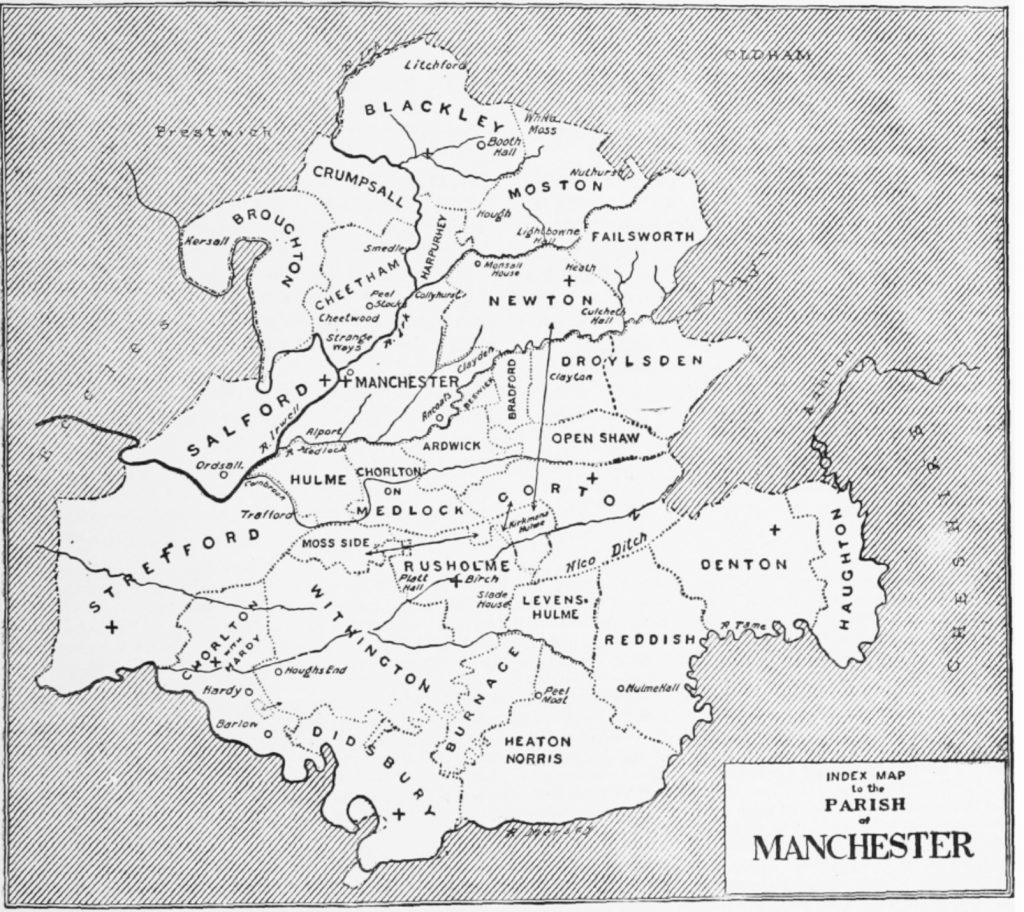

OPENSHAW, a township and a chapelry in Manchester parish, Lancashire. The township lies on the Manchester and Stockport canal, and on the Manchester, Sheffield, and Lincolnshire railway, 2 miles East by South of Manchester; contains a large village of its own name; and has a station on the railway, and a post-office at under Ashton-under-Lyne. Population in 1851 was 3759; in 1861, 8623. There were 1688 houses. The increase of population arose from the establishment of ironworks and chemical works. The manor belongs to G.Legh, Esq. There are a large cotton mill, weaving-sheds, extensive dye-works, a very extensive manufactory of railway carriages, and a depot for repairs of locomotive engines. The chapelry was constituted in 1840. The church was built in 1839, at a cost of £4,500 and is in the early English style; consists of nave, aisles, and chancel, with tower and spire; and contains 800 sittings. A Wesleyan chapel was built in 1864, at a cost of £2, 600 and is in the Anglo- Italian style; and contains 600 sittings.

Until about 1750, most people in Britain lived in small villages and farmed, raised animals, or worked as craftspeople. Farming families also spun wool or wove cloth in their homes to sell at the market. Men, women, and children worked hard every day of the week from morning until night, but most still struggled to earn a living. As the Industrial Revolution developed through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, more and more people moved away from their villages to work in mines and textile factories. A common working day in a factory was 12 to 14 hours long, with short breaks for meals. Workers laboured six days a week in 80 degree heat with machinery that needed constant attention. Overseers (managers) fined workers or threatened to fire them if they were not paying close attention to their work at all times. The factories were extremely dirty and dangerous, with low ceilings, locked windows and doors, and poor lighting. Workers risked losing limbs from loud, unguarded machines or getting serious throat or lung infections from the hot polluted factory air.

Charles Dickens, describes the rhythm of life for the factory workers in his book Hard Times: [They were] all equally like one another. All went in and out at the same hours, with the same sound upon the same pavement, to do the same work to whom every day was the same as yesterday and tomorrow, and every year the counterpart of last and the next.

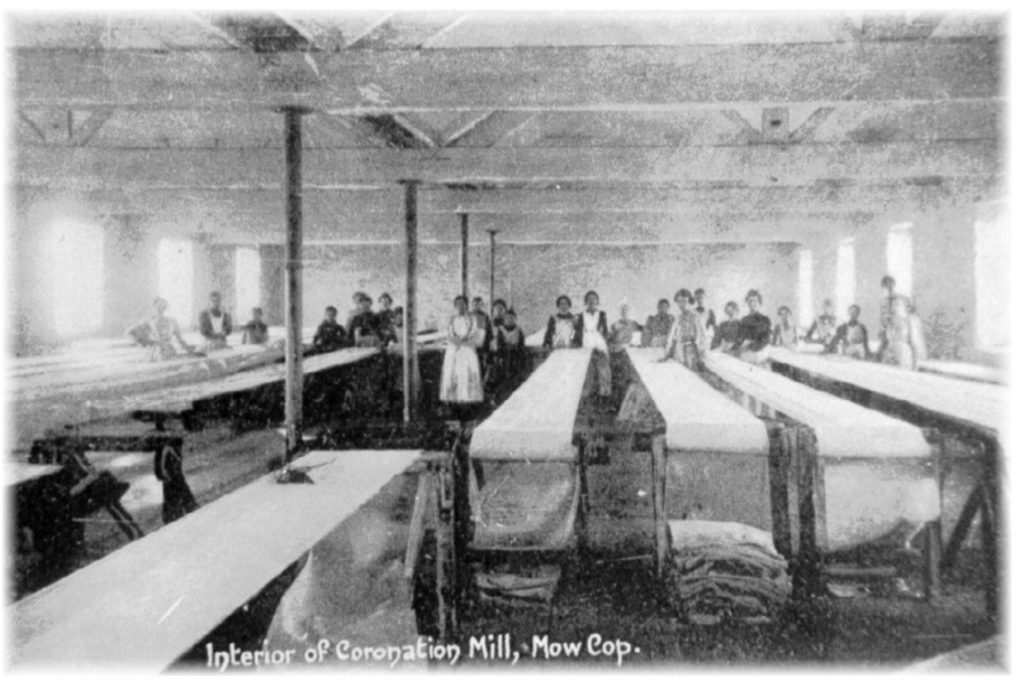

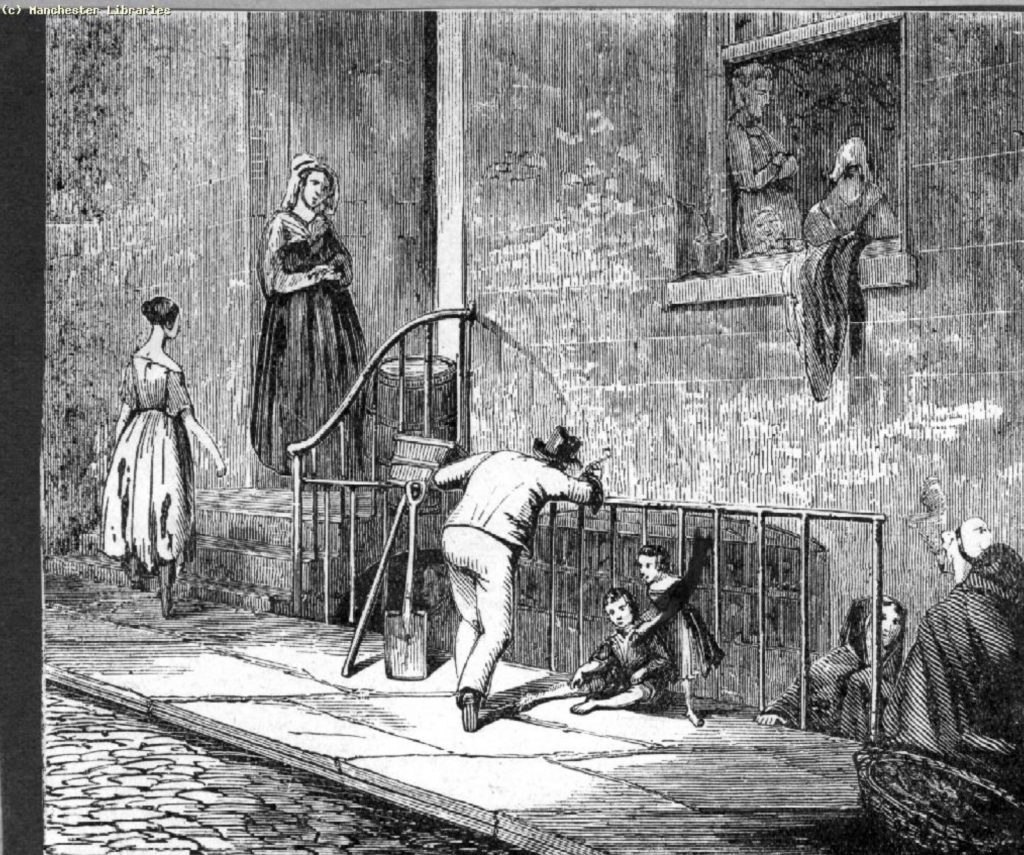

As John was in the process of relocating, whatever the reason, it was the importing of cotton, which began towards the end of the 18th century, that revolutionised the textile industry and Manchester in particular developed as the natural distribution centre for raw cotton and spun yarn. Richard Arkwright is credited as the first to erect a cotton mill in the city, quickly followed by the rapid spread of cotton mills throughout Manchester itself and in the surrounding towns. To these must be added bleach works, textile print works, and the engineering workshops and foundries, all serving the cotton industry. During the mid-19th century Manchester grew to become the centre of Lancashire’s cotton industry and was dubbed “Cottonopolis”. Young men and women poured in from the countryside, eager to find work in the new factories and mills. The mills paid relatively high wages and they also employed large numbers of children. As a consequence, families migrating to the city often saw a considerable rise in their incomes. John has on his Marriage Certificate the occupation of Dyer, a fact that is repeated all the way through his working life, except for one entry of a Fustian Dyer. A Dyer was employed in the textile mills to colour fabric prior to weaving. Fustian was formerly a kind of coarse cloth made of cotton and flax, used for making clothes for labourers. Later it became a thick, twilled cotton cloth with a short pile or nap, a kind of cotton velvet. Fustian is the old name for corduroy. A Fustian Dyer is a person who dyes the fabric. The picture below shows the interior of a Fustian Mill in Mow Cop, Cheshire in the 19th century, about five miles away from where John was living prior to his relocation to Manchester. Fustian mills required a long uninterrupted floor space on which the cutting tables could be erected. Some mills were purpose built and some were converted idle Silk mills where the owners removed valuable equipment to make way for the long fustian cutting frames. The floor boards were usually 4 inches (100mm) thick to allow for the constant walking back and forth of the fustian cutters.

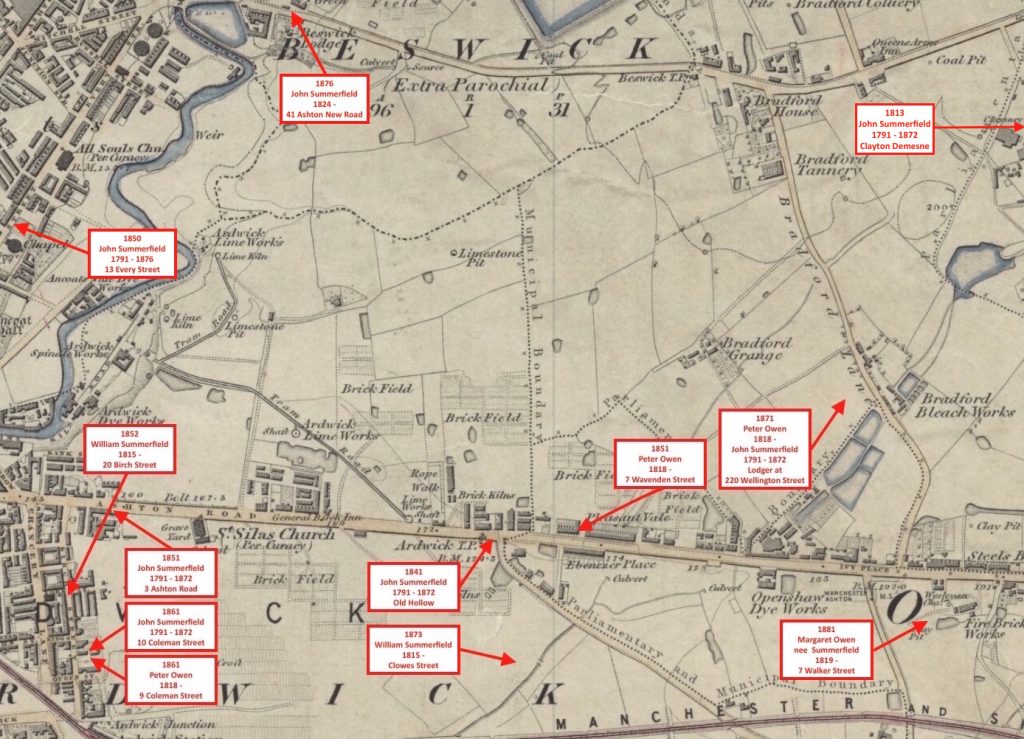

There is no address for either John or Hannah on their wedding entry, only that they were both of the parish of Manchester, St Mary, St Denys and St George, which at that time covered most of the Manchester area. They were married in the June of 1813 and their first born child, Samuel arrived in December. You don’t have to be that good at arithmetic to work out that the child was conceived before the marriage took place. According to the birth entry they were living at that time in Clayton Demesne, which at that time was part of Droylsden, see below. Openshaw, Ardwick, Chorlton upon Medlock, Ancoats and Bradford are all clustered together and where our family largely lived at that time.

We have encountered the word Demesne earlier in our story when it cropped up a number of times in those 17th and 18th century wills, in reference to the properties they were occupying. It is a Middle English word from the Old French demeine (later Anglo-Norman French demesne) ‘belonging to a lord’. Clayton is an area of Manchester 3 miles east of the City Centre on Ashton New Road and takes its name from the Clayton family who owned large parts of land around the area.

By 1815 when son William was born, John had moved to Openshaw, perhaps working in the Openshaw Dye Works, which was just down Ashton Road from where they were living. They were still there in 1817 when Mary was born and 1820 when Margaret came along. From the birth entries in the Parish Register of Manchester Cathedral for Elizabeth, John, Hannah, Sarah and Jane we know that the family lived in Openshaw during the years from 1821 to 1833. The first ever census in England was taken in June 1841 and John’s occupation is recorded now as a Fustian Dyer and he had the address of Old Hollow, Openshaw, Manchester, which I believe would have been somewhere along Ashton Road around the area of the Dye Works.

His occupation on 19th April 1846 is a Dyer, and the address is now 10 James Street, which is in Chorlton on Medlock, information provided on son William’s Marriage Certificate. James Street stood in the shadow of Chorlton Cotton Mills, which may well have been where John and sons William and John worked. No 10 was on the corner of James Street and Ormand Road and conveniently opposite the Lord Stanley Public House. The address three years later on 4th March 1849 is 13 Every Street, Manchester, this information provided on daughter Hannah’s Marriage Certificate, which is also the address provided on 30th June 1850 in son John’s Marriage Certificate. Every Street was a major thoroughfare in Ancoats and number 13 would have been at the southern end of the road and only about a ten minute walk from Ashton Road where they had moved from.

Ancoats has been described as the ‘first industrial suburb’ and as ‘the first residential district of the modern world intended for occupation by one social class’. In the 19th century, workers tended to live close the their employment, mainly because there was very little in the way of public transport, and what there was would have been well out of their financial reach. In Ancoats, much of the early 19th century property consisted of poor quality houses, often back-to-back around courtyards, in the shadows of the mills and other industrial buildings. The area had a very high density of population and conditions were reported to be grim. In 1870 it was said of Every Street that it “seldom wears a cheerful or gay aspect, but when a drizzling mist pervades the atmosphere of a winter’s morning’s general appearance is, to say the least of it, dull”. There are examples of terraces with a passage at the rear to enable the night soil cart to empty the privies on Every Street itself as well as on Long Street and Watson Street. Ancoats changed little between 1850 and 1900 when Kellet wrote that “the houses were of the cottage type with stone flags resting directly on a clay subsoil, unventilated with defective drainage, a third of them occupied by more than one family”.

John’s occupation in 1851 from the census of that year in March is as a Dyer living back in Ashton Road at number 3. His occupation ten years later on 10th November 1861 is still a Dyer and living at 10 Coleman Street. In 1871 aged 80 he is living with wife Hannah nearby as lodgers at 220 Wellington Street in the Manchester suburb of Bradford, the home of his daughter Margaret and her husband Peter Owen. Also staying with Margaret and Peter as a lodger in 1871 was John James Mayoh just five years old. This young boy was the son of William Mayoh and Hannah Yeardley and both have connections to our Summerfield family but we will come back to that. By the time of his death in 1876, aged 85, John had moved in with his son John living at 41 New Ashton Road, Bradford, Manchester.

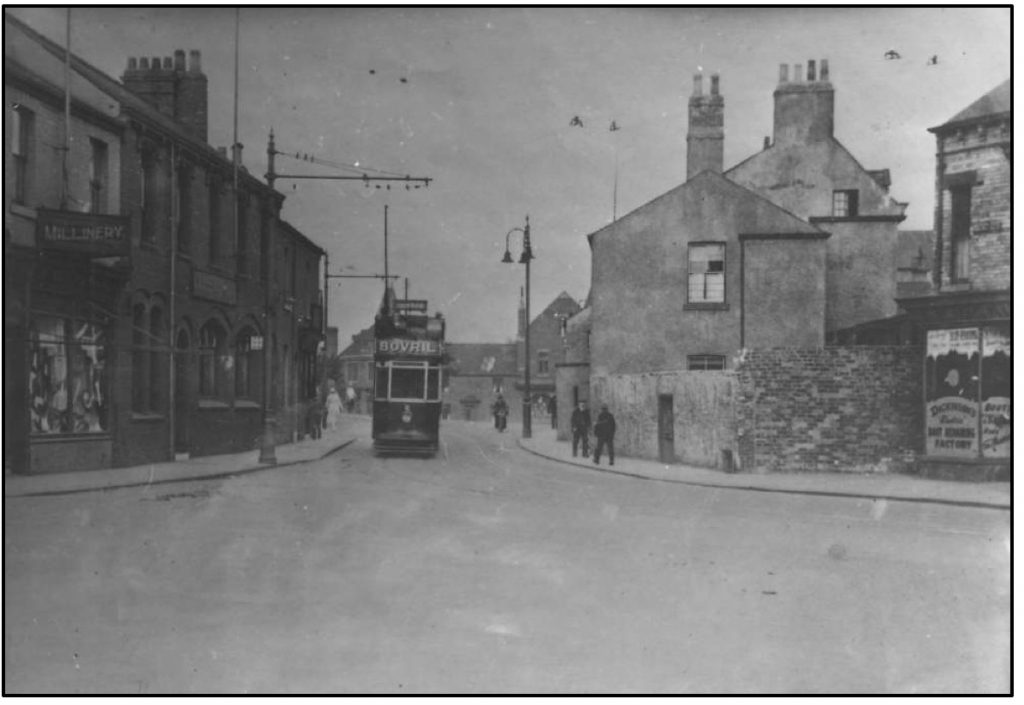

This picture from around 1910 shows Ashton Old Road looking west toward the city centre from the junction with Grey Mare Lane. It would have been much less developed in the 1840 / 50’s when John Summerfield and Hannah lived there, which can be seen from the 1848 street map earlier where Grey Mare Lane is at that time known as Bradford Lane.

The children of John and Hannah and their families:

SAMUEL SUMMERFIELD was born 5th December 1813, Clayton Demesne, Manchester.He married Nancy Mather 21st September 1835 at Manchester Cathedral. In the 1841 census they were living at Church Street, Newton, with Joseph Henry three years old and Peter one, their son James was born in November later that year. Samuel is still working as a Dyer. Later that same year and from Slaters Directories of Manchester we find Samuel still as a Dyer living in 2 Higginbothams Buildings, Chancery lane, Ardwick. In the 1850 directory he is now a Shopkeeper of Groceries, Ashton Old Road, Openshaw and again in 1852, 1853 and 1855. In the 1863 edition Samuel is back working as a Dyer, living in John St and still in Openshaw. A fourth son John was born after a gap of nearly ten years but sadly only lived for about nine months dying in May 1852. After the death of his wife Nancy in 1873 Samuel remarried in January 1875 at the age of 62 to a widow of 55 Alice Dawson in Albert Memorial Church, Collyhurst. On the marriage entry Samuel is now a Fustian Dyer, living at 310 Queens Road, presumably the shopkeeping didn’t work out. He died 9th January 1888 aged 74 and was buried in Christ Church, Bradford.

WILLIAM SUMMERFIELD was born in 23rd July 1815 in Openshaw, Manchester. He married Alice McCarty, daughter of John McCarty on 19th April 1846 in Manchester Collegiate Church (later Manchester Cathedral). More on this William in the next section.

MARY SUMMERFIELD was born on 5th June 1817 in Openshaw, Manchester. We have no further information on Mary until her marriage, she presumably lived with her parents and worked in the cotton industry for most of that time but it would be interesting to understand how she met up with her future husband Edward Yeardley. On the marriage entry both Edward and Mary are as described as minors although I believe she would be 21 two days later. Edward has his profession as a Weaver and they both have their residence as Whitefield, which is a suburb of Prestwich, a good eight miles from Openshaw. Although Whitefield had over earlier centuries been largely rural and supporting farming, but by the time of their wedding in 1838 there were a number of Cotton Mills and even a mine. Father of Edward is Thomas a Brick Maker who was also a witness to the marriage, probably because Edward was only about 18. Later information shows Edward as being born in Sheffield, which is likely as his father was living in Nether Hallam, Sheffield in the 1841 census.

Also in the 1841 Census newly married Mary and Edward are living with their first two children, Hannah and three month old John, in Old Hollow, Openshaw, just 5 doors away from her father John. Edward is now a Steam Weaver and they had four more children together, John, Elizabeth, Mary and Emma, the last being born in January 1848. Mary dies in the second quarter of 1850

In the 1851 Census Edward is recorded as a Widower and seems to have been promoted as he is now an Overlooker who would be someone whose job is to keep the shop working smoothly. What is known these days as Middle Management. He has most of his children with him although John who would have been ten is not present. Also staying with him is 66 year old Sarah Merton, classed as a servant and born in Whitefield, along with I am assuming is her 46 year old son John a visitor born in Prestwich. Sarah I imagine is a contact, family or friend from his time at Whitefield brought in to help with the children. By 1861 he is living at 7 Newton Street and has remarried to a young woman 15-17 years his junior depending on which version of his age you use. Hannah 21 and John 20, were living with their grandparents, John and Hannah Summerfield nearby in Taylor Street. It’s worth noting perhaps that Sarah the new stepmother would only have been 3 years older than Hannah, so perhaps not a match made in heaven.

MARGARET SUMMERFIELD was born about 1820 in Openshaw. She married Peter Owen, son of William Owen and Catharine Owen on 12th July 1840 in All Saints, Newton Heath, Witnesses on the Parish Register were James Owen, possibly a brother of Peter and Elizabeth Summerfield her younger sister who was still living at home with parents. Peter born in 1818 in Manchester has Blacksmith as a profession, father William was a Dyer same as Margaret’s father John. In the 1841 census Peter and Margaret are living in Catch Inn Lane, Barton-upon-Irwell which is about ten miles due east of Openshaw. Barton lies, unusually, on both sides of the Manchester Ship Canal/ River Irwell, it is also home to the Barton Swing Aquaduct a fantastic and still functional bit of Victorian civil engineering which carries the Bridgewater Canal over the Manchester Ship Canal. Peter’s occupation is recorded as a Smith and they probably moved there following work in his profession. They have with them their first child Peter but they have the wrong age recorded. Peter was born on the 8th April 1840 in Openshaw, three months before they were married, and the name in the St Barnabus Parish Register is Peter Summerfield. Not conclusive that Peter Owen was the father but I think very likely. They must have stayed in the area for a few years because their second child Elizabeth was born in 1842 at Winton which is just a mile away from Barton.

The remaining children were all born in the Openshaw area. They had a lot of children, perhaps ten or more, I lost count in the censuses as they were growing up and moving on as more were being born. In 1871 though there were a couple of new additions to the family group, five year old John James Mayoh. This unfortunate young boy was the son of William Mayoh, who had married Hannah Yeardley, remember that name? She was the eldest daughter of Mary and had moved in with her grandparents when Mary died and father Edward remarried, but more of Hannah and her son later. Also living with Margaret and Peter was her parents, John now 80 and Hannah 77. Peter died in 1874 but Margaret was still there in the 1881 census with three of her children and a couple of boarders. I think she died in 1889.

ELIZABETH SUMMERFIELD was born on 4th November 1821 in Lancashire. She was a witness at the marriage of her sister Margaret to Peter Owen at Newton Heath in 1840, she was still living at home with her parents in the census of 1841 and employed as a Cotton Weaver. Elizabeth was not to live much longer, she died on 30th April 1842, her death certificate the cause of death as Inflammation of the Bowels, she was just 21 years.

JOHN SUMMERFIELD was born in 1824 in Openshaw, Lancashire. His occupation at 17 in the 1841 census is that of a Bleacher. Which he still was when he married Matilda Dutton, 23, daughter of John and Margaret Dutton on 30th June 1850 in Manchester, St Mary, St Denys and St George. In the 1841 census we have a John Dutton a Blacksmith and Margaret Dutton both 50 years old with three daughters Amelia 20, Caroline 15 and Matilda 10 whose occupation is as a Milliner. This does match up with her Bonnet Maker occupation in 1851. If this is the correct connection I wonder if the age discrepancy is something to do with wishing to appear younger perhaps. It does look as though Matilda already had a child at the time of her marriage, Elizabeth, born in 1849 and was pregnant with her second child, Caroline, born later that year in September. No evidence whether or not John was the father of the children, but he certainly brought them up as his own anyway. They were definitely a couple at that time because they were both the witnesses at the marriage of John’s sister Hannah and Robert Gregory on 4th March 1849. They had five more children including the twins Samuel and Sarah Jane born in 1863. John died in 1901 at 76 and Matilda in 1910 at 82 or 78 depending which version you use.

HANNAH SUMMERFIELD was born in 1828 in Manchester. She married Robert Gregory, son of John and Elizabeth on 4th March 1849 in Manchester, St Mary, St Denys and St George. Robert was born in 1827 in Manchester. No difficulty how they might have got to know each other as Hannah was living in the family home at 13 Every Street and Robert with his at number 26. In the 1841 census Robert and his father are both listed as working as Laborers, but by the time of his marriage they are both Boilermakers. Their first child Robert was born the following year in Openshaw but by the time of the 1851 census in June they were living in Bromley St Leonard, Middlesex, a bold move by any stretch of the imagination.

BROMLEY-ST.-LEONARD, a parish in Poplar district, Middlesex; on the river Lea, the Limehouse cut, and the North London and Eastern Counties railways, 3¾ miles east of St. Paul’s, London. The slow growth there of the 1840s was followed by the major boom of the century, in the 1850s and early 1860s. This was part of a wider economic expansion, reflected in Poplar by the development of the shipbuilding industry, further fuelled by orders during the Crimean War of 1854–6 and the American Civil War of 1861–5. These conflicts greatly increased the demand for ships, as did the adoption by the major navies of iron steamships to replace wooden sailing ones. The numbers employed in shipbuilding and marine engineering on the Thames had increased from an estimated 6,000 men in 1851 to 27,000 in 1865, but fell to 9,000 by 1871, and to 6,000 by 1891

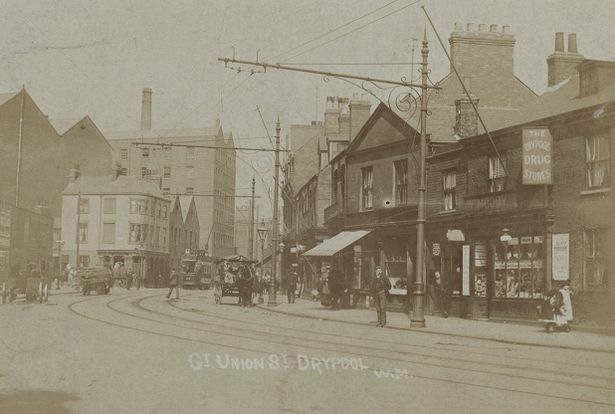

Their second child Henry was born whilst they were in Middlesex, but by the time of John W in 1859 they had moved again, this time to Drypool, Kingston upon Hull, and were still there at census time in 1861 and when Elizabeth was born in 1865. Drypool – “dried up pool” – was a distinct community, a village first mentioned in the Domesday Book in 1086. By the time Victoria Dock opened in 1850, Drypool had been swallowed up by the city. For many years, it remained a strong community with a village centre clustered around St Peter’s Church and the green. Here the famous Drypool Feast was held every year in the week after Hull Fair. Robert was obviously doing well as his occupation is now recorded as a Foreman Boilermaker, and they have a live-in House Servant helping Hannah run the home. Also there on the night of the census was the mother of Robert, Elizabeth, who may well have been living there, and Hannah’s sister Sarah who was to marry William Bell later that year back in Manchester.

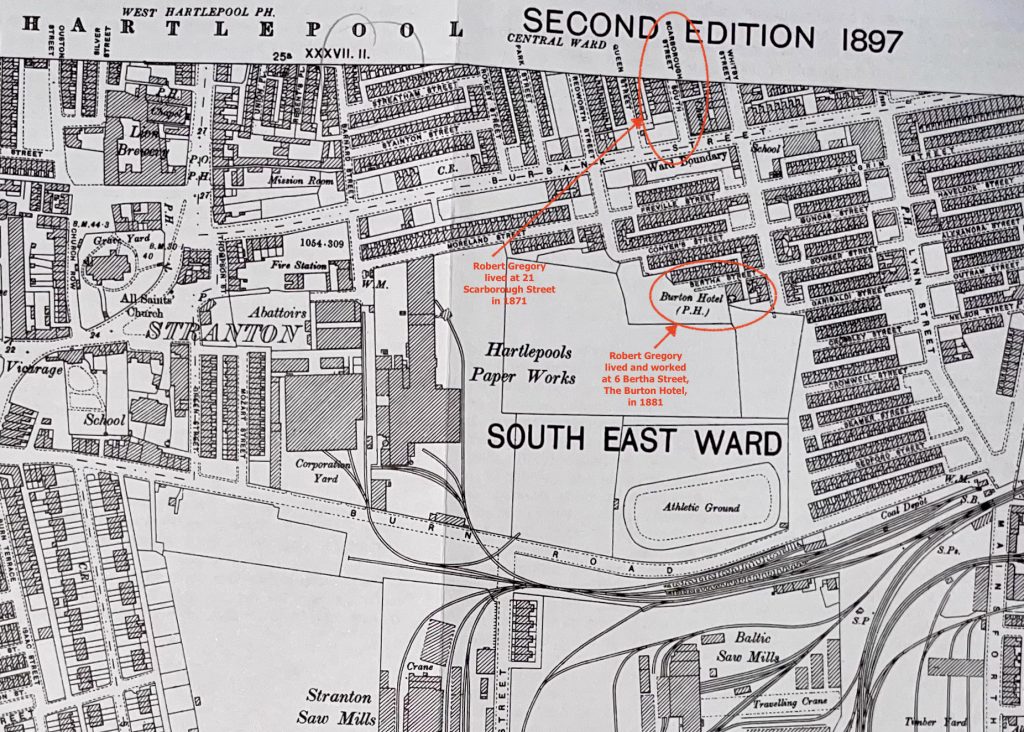

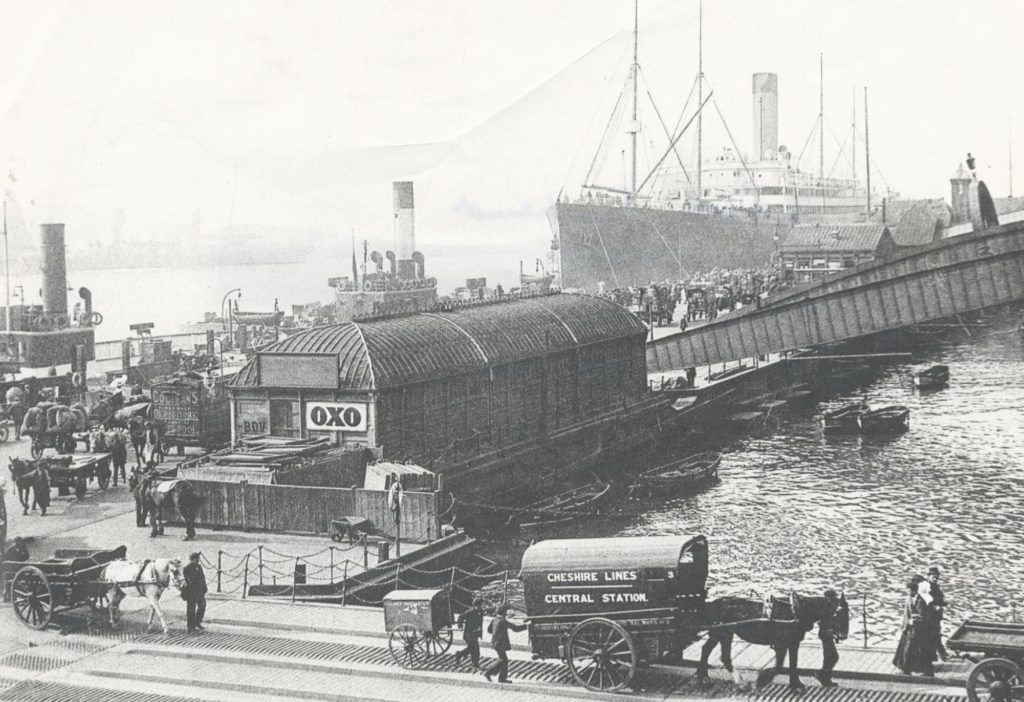

Sometime between the birth of daughter Elizabeth in 1865 and the census in 1871, Robert and his family made the move north to Shipbuilding town of West Hartlepool. Robert obviously kept a good eye, or ear, on where the employment prospects for his skills lay because it was about this time in 1868 that the West Hartlepool shipbuilding firm of Dentom, Gray and Co. were expanding launching the ‘Ouse’ there in 1867. By 1870 over 1000 men were employed by them and 15 ships were launched by them in that year. A new firm of William Gray and Co. was set up in 1874 and prospered to such an extent that in 1878 it was awarded, for the first time, the Blue Riband for the maximum output of a British yard. Here then is a new town, with a growing shipbuilding industry and docks that would soon be the third busiest in the country.

In the 1871 census Robert, now 44, is a Foreman Iron Ship Builder, living at 21 Scarborough Street, which was in the ancient Hartlepool parish of Stranton. His two sons are also in the business as well, Robert an Iron Ship Plater and Henry an apprentice. They also had staying with them a Boarder, 22 year old William Campbell, an Iron Ship riveter. I find it interesting that many of the wider Summerfield family lived in and around this same area. You will see the same street names come up time and again. My own parents for example lived in Scarborough Street twice, first in 1936, shortly after they were first married, and again with me and my sister for a short while in 1948.

Something changed for the Gregory family during the following ten years because by the time of the 1881 census Robert is now a Publican running the Burton Hotel in Bertha Street, within a couple of hundred yards of where he was living ten years earlier. He seems to have given up his very successful profession as a shipbuilder. Perhaps the work wasn’t as plentiful as it had been or maybe he just wanted a change of lifestyle. The next few years however will have taken their toll on him. His wife Hannah died in May of 1883 and his son Robert, after getting married in 1877 died just a few months later at just 32 years of age. In 1891 he living with his 26 year old widowed daughter Elizabeth at Smith Street in Old Hartlepool and at 64 years of age back on the tools as a Boiler Plater. He died in 1897.

SARAH SUMMERFIELD was born on 9th March 1830. She married William Bell, son of George Bell on 25th December 1861 in Manchester, St Mary, St Denys and St George, Manchester. William was born about 1830 in Manchester to George and Rebecca. He was living with his family in Malaga Street in 1845 and still there in 1861 when he married Sarah on 25th December 1861. Also present, as witnesses, were Sarah’s sister Jane and her husband James Mayoh, who had married just six weeks earlier. William’s occupation is recorded as a Carter as was his fathers. Carters were drivers of usually horse-drawn vehicles used for transporting goods, often employed by railway companies for local deliveries and collections of goods and parcels. A modern day ‘white van driver’. A Carter typically drove a light two wheeled carriage such as a pony and trap, or even a donkey. This occupation is most likely the reason that they lived all their married life in the streets around London Road Station (what is now Manchester Piccadilly). They don’t seem to have had any children.

JANE SUMMERFIELD was born on 1st December 1833 in Openshaw, Manchester. She died 1oth February 1877 in Whitby Street, West Hartlepool. She married James Mayoh, son of James Mayoh and Jane Greenhalgh on 10th November 1861 in Manchester Cathedral. James was born in 1838 in Turton, Lancashire. He died in 1882. In the 1861 Census Jane was living with her parents in Taylor Street, Bradford and two doors away lived John and Charlotte Mayoh and their three children. They also had staying with them as boarders William and James Mayoh from Turton, Lancashire. Charlotte Mayoh, formerly Greenhalgh, was the cousin of James and William Mayoh, her father John Weaver Greenhalgh being the brother of their mother, formerly Jane Greenhalgh, all from Turton in Lancashire. Jane was to marry James in Manchester on 10th November later that year, and they were both witnesses at the marriage of Sarah in the December.

Also staying with her parents in 1861 was Hannah Yeardley 21 and her brother John 20, the children of Jane’s eldest sister Mary and husband Edward. Mary had died in 1850 having had six children with Edward. He had remarried to Sarah Ryder in 1856 and had two more children with her. Two more of the six Elizabeth 18 and Emma 13 were living with father Edward and new wife Sarah at 7 Newton Street, Openshaw. There was no indication of where the remaining two children Thomas 20 and Mary 15 had gone to at this time, but it is worth noting perhaps that Sarah the new stepmother would only have been 3 years older than Hannah. Hannah marries the other brother William Mayoh in 1864 in St Andrews (Drypool) Hull. Hannah’s first child Arthur however was born 29th April 1862 in Manchester, possibly Williams child as he was living just a couple of doors away, but not named on the birth certificate. The witnesses at the wedding were James Mayoh, Williams brother, and Jane Summerfield, now Mayoh, Hannah’s Aunt.

Earlier we learnt that Hannah Summerfield, now Gregory, lived with her husband and children in Hull for at least ten years around this time, and its my conclusion that both Jane and James Mayoh and William and Hannah all settled in Hull first and then the North East pursuing occupations in shipbuilding, following the lead set by Hannah and her husband Robert. In the 1871 Census Jane and James are living at 36 Albert Street, Stranton, West Hartlepool, just a few hundred yards away from where sister Hannah is living. James is a Labourer in the Shipyard, and they have James 63 year old widowed mother also living with them. Unfortunately Jane is to die still a young woman in February 1877 whilst living in Whitby Street, West Hartlepool. James moved back to Manchester and remarried, but also dying relatively young in 1886.

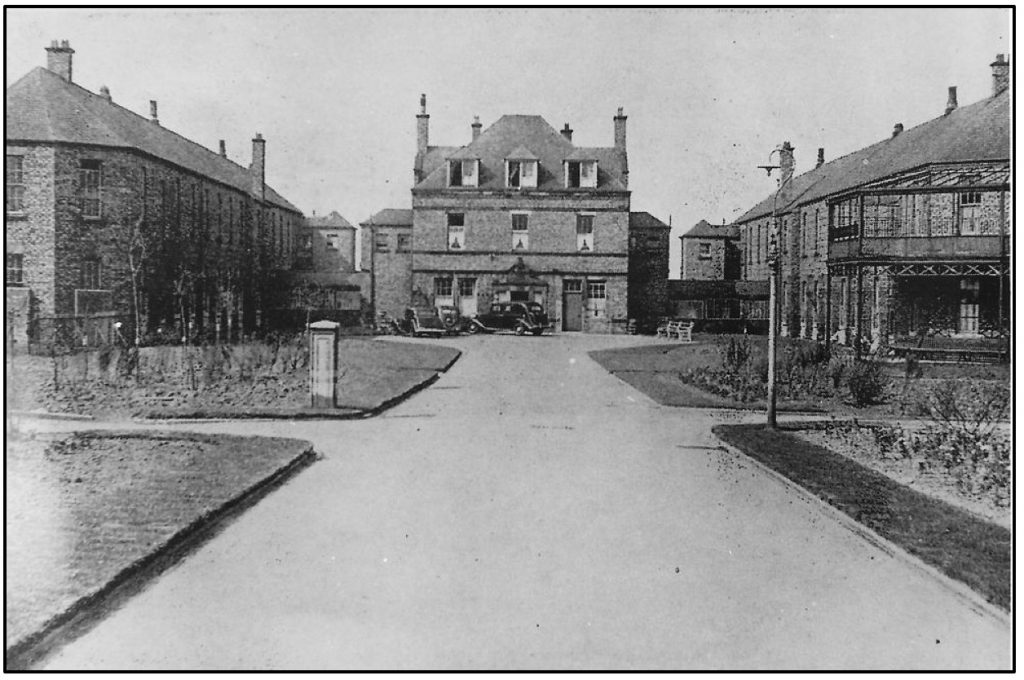

Although Hannah Mayoh nee Yeardley is not a direct descendant, her unfortunate story is intertwined into the lives of our family members. When living with her grandparents John and Hannah in 1861 there would only have been six years between them, so it’s highly likely that they could become friends. Jane was a weaver in the Cotton Mills and Hannah a Charwoman. The occupation covers a fairly wide range of activities, but the vast majority were ‘cleaners’ – women going around cleaning other women’s houses. With the two Mayoh brothers living a couple of doors away in Taylor Street and also working in the cotton industry as Cotton Dyers, there would have been many opportunities for them to socialise together. At this same time, the older sister Sarah was visiting sister Hannah in Hull and perhaps came back home with stories of the job opportunities there was to be had in the burgeoning shipbuilding industry. Jane and James were witnesses at Hannah’s marriage in Hull in 1864, so could possibly have moved there as well. But we do know they both moved again to the North East. Hannah and William with their now three children to Sunderland and by 1871 Jane and James to West Hartlepool. Sadly, Hannah dies in 1868 whilst at 24 Brooke Street, Sunderland, and William 12 months later leaving three children with ages of three, four and seven years. The children appear to be destitute at that time in 1869, perhaps because neither Jane and James Mayoh or Hannah and Robert Gregory had yet to arrive in the North East. John James, the youngest was by 1871 living with his Great Grandparents John and Hannah Summerfield who were by then themselves living with their daughter Margaret Owen and her family in Wellington Street, Bradford, Manchester. Arthur and Mary Jane in 1871 were residents of Hartlepool Union Workhouse, Holdforth Road, Throston. As an observer from another generation I feel more than a little disappointed that somebody in this quite big family couldn’t find room for these two small kids fallen on hard times. They seem to have done OK all the same. Arthur stayed around the area, getting married, having a family and pursuing a career in the shipbuilding industry. Mary Jane was adopted from the Workhouse in 1881 by a family from Grimsby.

These buildings later became the Howbeck Infirmary and later again the Hartlepool General Hospital where I was born in the early hours of 8th May 1947. So I suppose you could say that I was born in the Workhouse. I remember as a troublesome child quite often being told by my mother that I would drive her into Howbeck, which was referring to the fact that the Howbeck Infirmary had in it’s past contained a ward for mentally unstable patients (or as they were termed then ‘Lunatics’), and hence its other name ‘the Looney Bin’.

My 2nd Great Grandfather.

WILLIAM SUMMERFIELD was born in 1815 in Lancashire. He married Alice McCarty, daughter of John McCarty on 19th April 1846 in Manchester Collegiate Church (later Manchester Cathedral). William Summerfield and Alice McCarty had the following children:

- ELIZABETH SUMMERFIELD was born on 28th December 1848. She married Ambrose Walton, son of James Walton and Sarah Porrit on 23rd December 1873 in Manchester, St Mary, St Denys and St George. Ambrose was born in January 1851 in Hill Street, Bingley, Yorkshire.

- JOHN SUMMERFIELD born December 1850 in Openshaw and married Elizabeth Jane Musgrave in Hartlepool in 1876.

- WILLIAM SUMMERFIELD was born on 15th October 1852 in Manchester. He died on 8th June 1929 in 39 Eden Street, West Hartlepool, Durham. He married Isabella Laurie, daughter of William Laurie and Catherine Dobie McLeod on 24th October 1881 in Stranton, West Hartlepool. Isabella was born in 1855 in Glasgow, Scotland. She died in 1914 in West Hartlepool, Durham.

In the 1841 census William, now 26, is recorded as being a Fustian Dyer, the same as his father John, and also a Curtain Dyer, he was still living at his parents home in Old Hollow, Openshaw. By the time of his marriage to Alice in 1846 he had moved with his family to 10 James Street. Alice is living with her parents in Cobourg Street, which is less than a mile away toward the centre of the city just off London Road. Alice’s father John and mother Margaret, both worked in the cotton industry and it is perhaps because of their similar employment that the families met and the two youngsters became friends.

This 1850 painting of London Road, Manchester, by Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait (1819-1905), gives a vivid impression of the city in its early Victorian heyday. This view is taken from the junction with Auburn Street and shows London Road station at the top of the ramp in the background to the left. The station was originally built as Store Street Station by the Manchester and Birmingham Railway in 1842, before being renamed London Road Station in 1847 and became Manchester Piccadilly in 1960.

The McCarty family were from Cork in Ireland and Catherine, elder sister of Alice was born there in 1815, but the family had moved by the time Alice was born in 1817 because her birth is registered in Dalston, a village about four miles south of Carlisle in Cumberland. This place of birth was confirmed by Alice in the 1841 Census. The occupations of John we know where as a Spinner and Hand Loom Weaver which might account for the family’s emigration to Cumberland. There was a cotton textile industry in Ireland in the early 19th century with Belfast and Cork among two of the major centers for this industry. However, it’s manufacturing output peaked around 1825 and this might have been the trigger for moving to greener pastures. The spinning of cotton in Dalston, like Cork, grew out of what had previously been a domestic and cottage industry. It looks as though within a few years they had moved again to Manchester as that is where younger sister Elizabeth was born 1821.

William and Alice had their first child, Elizabeth, in 1848 and they were still living in Ardwick. William is still working as a Dyer, as he was in 1851 according to the census taken that year, but now living in Ashton Road, close to Duckworths Buildings, not very far away at all from his father John who was at that time in number 3 Ashton Road. There is also a new addition to the family, born in December 1950 and named John after his grandfather. By October 1852 when son William is born they have moved to Birch Street, which is at the western end of Ashton Old Road and even closer to his father. On the Birth Certificate for both John and William, his mother Alice had recorded as her maiden name Carter, rather than McCarty, which might have been a nod toward the growing disaffection that the locals had for the massive influx of Irish workers. Sadly another premature death was to occur with Alice dying of Consumption, or Tuberculosis as we now know it, on 20th March 1853, they were still living in Birch Street. The informant for the death records was Ellen Heywood of North Street, which is a short distance away in Ancoats, who was present at the time of the death. As the children would have been around three years, two years and William at just five months when their mother died, perhaps this lady was some sort of childminder/housekeeper brought in to allow William to carry on working as Alice’s health deteriorated. She, or someone else in a similar capacity, would certainly have been needed afterwards if William was going to continue earning. I have William in an entry in the 1855 Slaters Trade Directory, which records William as being a Dyer and now living at Shatwells Buildings, Ancoats Hollow. Possibly working at the nearby Ancoats Bridge Dye Works. In the same year I also found him in the Manchester Rate Books living in a cellar of a property owned by Samuel Duckers in Ashton Road. The Rate Books were a record of the levies or taxes that property owners had to pay as their contribution to the costs of supporting the poor and needy of the district, such as Poor Relief payments and Workhouses. Living with his family in a cellar was not uncommon in this era but was a big drop in standards for William and an indication of how hard times were for him since Alice had died.

That Rate Book entry in 1855 is the last evidence I have been able to uncover on the life of my Great Great Grandfather William Summerfield, he would have been just 40 years old. He is recorded on the three marriage certificates of his children, but that is no indication that he was in fact present. At the marriage of Elizabeth his occupation is recorded as a Carpenter, which I found strange and did send me off down another line of enquiry as to whether I had found the correct Elizabeth. There is another William Summerfield around at the same time who is a Joiner but I have convinced myself that there is no connection. My suggestion is that after nearly 20 years working in Service Elizabeth was just ‘buffing up’ her history for the benefit of her new husband. When his son William married he is recorded simply as a Labourer and when John married as a Weaver, not the Dyer he was always recorded as. Although his grandfather John McCarthy was a Handloom Weaver.

Elizabeth is found in the 1861 Census at the tender age of 12 as a servant in Gorton Place, which looks like it is a laundry business, and ten years later in the 1871 Census she is still ‘living in’ now as a servant to Alexander Thomson, Independent Minister of the nearby Rushden Road Chapel, and his family at 27 Portland Crescent. Ambrose Walton, who was a Printer from Keighley in Yorkshire, and married Elizabeth in 1873, his address given on the marriage certificate is Clowes Street, Hyde Road, which is also given for Elizabeth. We should be a little wary of an address which is the same for both parties as this was often used to avoid paying two sets of banns fees to the church if one or the other party resided in a different parish. Marriages usually took place in the parish of the bride. Mary Ann McConnell was a witness at the marriage, and she was also working as a servant with Elizabeth for Alexander Thomson in the 1871 census. Elizabeth and Ambrose moved shortly after their marriage and by 1879 had settled in Blackburn, Lancashire where they spent the rest of their lives.

Working on the loosely informed view that the Father, William, has perhaps died or absconded, we have the three children seeming to be largely fending for themselves. I found an entry in the 1861 census for a John Summerfield aged 12 in the Chorlton Union Workhouse, Withington, which is just down the road from Openshaw. Nothing further to corroborate this as our John Summerfield other than the mitigating situation he might have been in. I have also found a John Sommerfield in the Register of Apprentices’ Indentures for November 1866. Age when bound was 16 years, Date of Indenture was 12.11.1866 and Bound for 5 years until age 21 to Mr JJ Hobbs of Hull. He was on the Fishing Smack Majestic, Number 45114, and enrolled at Hull. The reason I have given some credibility to this ‘find’ is that he was certainly a Mariner as his later life confirms, and the fact that his father’s sister Hannah lived at that time with her husband, employed in the shipbuilding industry, and family in Hull. A strong connection I thought, particularly as they all live in Hartlepool a few years later. John was to marry a local girl in Hartlepool in 1876

Courtesy: © Hull Museums

But son William, my Great Grandfather has, to date, been impossible to trace, from his birth in 1952 right up until I find him as a Mariner in the 1881 census, and that singular failure has occupied many, possibly even hundreds, of hours of research.

A possible reason for the difficulty in tracking down ancestors and their movements, both in this scenario with William but also in other areas of the story, is that the spelling of the name has quite frequently changed over the three hundred odd years that I have covered. Often causing me to research down a totally unconnected family line until the error has been realised. It’s obviously not intentional on the part of the chroniclers to record the wrong details but what I think might have happened was due to illiteracy on the part of the subjects. Most of the family entries, particularly in the earlier years, have just an ‘x’ in place of their signature, usually with the words “this the mark of”. If therefore the parish clerk or whoever is asking for their name and they reply with for example ‘Summerfield’, it is then up to that person how they in fact spell the name. And, of course, the subject can’t correct that spelling, even if they knew what it should have been because they can’t read or write. After many, many hours trawling through records, this is the only practical conclusion I have arrived at for so many inaccuracies in the details.

Another potential difficulty for William during this period might have been the lack of employment due to the Cotton Famine. The year 1861 was a good one for the American cotton harvest, and cotton exports to Britain and elsewhere continued until about mid-December. In late 1861, hoping to force Britain and other European countries to ally themselves with the Confederacy in the U.S. Civil War, some confederate states and cotton plantation owners announced an unofficial cotton ’embargo’ that sharply curtailed exports to these countries. After stockpiled cotton was depleted in 1862, British mill owners addressed the shortage by reducing work hours and by seeking alternative cotton sources like India and Brazil. But by late 1862, mills started to close and by 1863, thousands were without work. As the Northern blockade and cotton embargo continued, Southern leaders were sure that the economic losses incurred by Britain would force the country to enter the war in favor of the South. But despite the massive hardships brought on by the lack of cotton, Britain also depended on wheat from the northern U.S. states, and supplied the Union with the tools to make war: guns, ammunition, and ships. So rather than enter the war, Britain responded internally by raising huge sums for ‘relief’, and though not until 1864, enacted a Public Works Act to put thousands to work building parks and other public infrastructures.

This is largely the end of the story in Lancashire for us, obviously more distant family members continued to live there and probably still do. But we must now turn our attention in the next section to the town of my birth and the families in Hartlepool.